I think often about the absurdity of those drills. Duck and cover, they told us, as if a wooden desk manufactured in Grand Rapids could shield a seven-year-old from the splitting of atoms, from the unleashing of the sun itself onto suburban playgrounds. We practiced dying the way other children practiced piano scales—with reluctant precision, again and again, until the motion became muscle memory. Heads down, hands clasped behind necks, knees tucked under flimsy furniture that wouldn't survive a particularly enthusiastic game of tag, let alone the end of the world.

The teachers smiled their bright, brittle smiles. It's just a game, they said, but their voices carried the tremor of people who had seen the newsreels from Hiroshima, who understood what those shadows burned into concrete actually meant. They were teaching us to participate in our own theater of the absurd, a performance where everyone knew the ending but pretended the play might have a different conclusion this time.

What strikes me now is not the futility of the gesture—though it was, magnificently, futile—but the precision with which it calibrated our terror. We learned to fear not just death, but a specific kind of death. Not the death that comes from old age or illness or accident, but death as a policy decision. Death as a Tuesday morning surprise. Death that arrives faster than breakfast, carrying with it the obliteration not just of you but of everything you've ever seen or touched or loved, and everyone else's everything too.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, I watched the adults with the intensity of a mini anthropologist studying a newly discovered tribe. They moved differently. Spoke in truncated sentences. Listened to the radio with the kind of attention usually reserved for prayer. My mother, who normally approached world events with the detached interest of someone reading about distant civilizations in National Geographic, suddenly began checking the locks twice, as if Soviet missiles could be deterred by deadbolts.

I didn't understand then that we had wandered to the very edge of the world and peered over. Thirteen days of Kennedy and Khrushchev playing chess with civilization as the stakes, each move bringing us closer to a checkmate that would leave the board empty. The adults knew. They could feel the weight of that red button, even from thousands of miles away, pressing down on their shoulders like a physical thing.

Between the duck-and-cover years and the Cuban Missile Crisis came the great American enterprise of monetizing apocalypse. Fallout shelters became the must-have accessory of the suburban middle class, advertised in Life magazine between recipes for tuna casserole and testimonials for washing machines. The sales pitch was irresistible in its simplicity: survival as a consumer choice, the end of the world as a lifestyle upgrade.

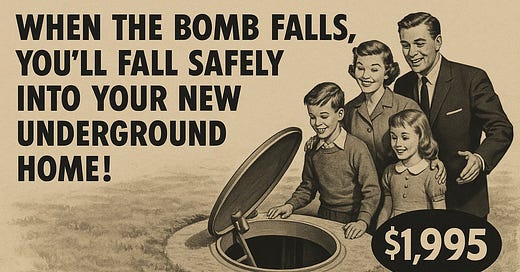

You could buy your way out of extinction, the brochures promised. For $1,995—about the cost of a new Buick—you could purchase a corrugated steel tomb for your backyard, complete with air filtration system, chemical toilet, and enough space for a family of four to contemplate their neighbors' incineration in relative comfort. The deluxe models came with AM/FM radio and fold-out beds, as if nuclear war were merely an extended camping trip with higher radiation levels.

The advertisements showed smiling families gathered around their shelter's Formica table, the children's faces bright with the promise of adventure. "When the bomb falls," read one particularly memorable tagline, "you'll fall safely into your new underground home!" The copywriters had managed to make the end of civilization sound like a real estate opportunity.

What they didn't advertise was the mathematics of survival. How many families could afford the ticket to the post-apocalyptic future? How many couldn't? The fallout shelter industry had created a new kind of class system: those who could buy their way into tomorrow and those who would be left to face it unprotected. Suburbia began to eye itself differently. The Muellers next door—did they have a shelter? The Nguyens across the street—were they looking at your children and calculating how many mouths their food reserves could feed?

The logic was as brutal as it was inevitable. If the bombs fell, your neighbors would become your competitors. Their children would be mouths competing with your children for the same finite resources. The shelter salesmen understood this perfectly. They sold not just protection but permission—permission to lock your door when the world ended, permission to let others die so that you might live.

I think about Mrs. Randolph, who lived three houses down from us, standing in her driveway that autumn afternoon in 1962, watching the contractors install the Wilkinson’s new shelter. She had four children and a husband who worked at the plant. They couldn't afford the deluxe model. They couldn't afford any model. She stood there with her arms crossed, watching the dirt pile up in her neighbors' yard, and I saw her doing the calculation that would keep her awake for months afterward: when the sirens sounded, where would her family go?

The shelter era ended not because the threat disappeared but because we couldn't sustain the logical conclusion of our own premise. A survival strategy that required abandoning your neighbors was no survival strategy at all—it was a confession that the civilization we were trying to preserve had already died, buried under the weight of our own fear and marketed at wholesale prices.

The eighties brought us new language for the same old terror. Mutual Assured Destruction—MAD, they called it, with the kind of bureaucratic humor that makes you wonder if Orwell was being optimistic. We marched for peace while Reagan spoke of Star Wars, not the movie but something more ambitious and infinitely more expensive: the militarization of space itself. The protesters carried signs reading "Nuclear Freeze" while the Pentagon carried budgets for weapons that could crack the planet like an egg.

I remember thinking then that we had built ourselves into a corner from which there was no dignified exit. Like children who had dared each other to hold lit matches until someone flinched, except the matches were hydrogen bombs and flinching meant admitting that perhaps the entire enterprise had been madness from the start.

Now we find ourselves in 2025, and the children of those duck-and-cover drills are the ones making the decisions. The generation that practiced hiding under desks is now deciding where to point the missiles. There's something darkly poetic about this, the way trauma cycles through decades like a virus that never quite clears the system.

The president operates from the realm of the cinematic, where problems are solved with decisive action and dramatic music swells at moments of resolution. But nuclear war is not a Western. There is no High Noon moment, no mano a mano showdown where the righteous prevail and the credits roll. There is only what Herman Kahn called "thinking about the unthinkable"—the slow, methodical calculation of megadeaths, the bureaucratic parsing of acceptable losses, the reduction of human civilization to a series of target coordinates.

Consider the logic: if you bomb a nation into rubble, if you kill their children and demolish their hospitals and turn their cities into glass, what exactly do you expect their response to be? Gratitude? A thoughtful reconsideration of their foreign policy positions? The incentive structure of nuclear warfare is perfectly, terrifyingly clear: once you have nothing left to lose, there is no reason not to take everyone else with you.

This is what keeps me awake now, in the small hours when the world feels most fragile. Not the possibility of nuclear war, but the probability of it, the way it seems to follow from our current trajectory with the inevitability of water flowing downhill. We have intelligent people—people who read the briefings, who understand the mechanics of fission and the mathematics of fallout patterns—quietly stocking their basements with potassium iodide tablets and radiation detectors. They are not conspiracy theorists or doomsday preppers; they are simply people who can read the writing on the wall and have decided that hope is not a strategy.

The red button sits in rooms with men who believe they are starring in their own heroic narratives. They see themselves as Gary Cooper in High Noon, not as the children we all were, crouched under desks, learning to practice our own annihilation. They have forgotten the lesson that terrified us so effectively all those decades ago: that there are some games where everyone loses, some dares that end with no one left to collect the winnings.

The desk was never going to save us. We knew that even then, in our child-wisdom that cuts straight through adult delusions. The desk was just a prop in a performance designed to make us feel that someone, somewhere, had a plan. That survival was possible with the right technique, the correct posture, the proper attitude.

But the truth was simpler and more terrible: we were teaching children to rehearse the end of the world. And now those children have grown up to inherit it.

For a better understanding of how much peril we are in, a short read/listen:

The Trojan Horse Will Come for Us Too

Image ©2025 Gael MacLean

Wow. "We practiced dying the way other children practiced piano scales"

That lands hard.

The PTA discussed exposure to sex and violence on TV while preparing us for a nuclear attack. Do you think child psychologists figured the drills somehow reassured us we had power? Help us decide that Jimmy - the future anarchist dangerously sitting next to a glass window should never be trusted to lead, protect, or defend people? We're back to the familiar question - better to be blissfully ignorant, or informed when you have no control?